Over the years I have worked with many people who had hip replacement surgery. Many of these clients discovered high metal levels in their bodies from metal-on-metal (MoM) hip components. Often the person would let me know that she had her metal levels checked and that the blood work came back with abnormally high readings of cobalt, chromium, or other metals. Still, the treating physician would occasionally dismiss the blood work results. At least one doctor told a patient, “no one knows the effects of higher metal levels on the body. We haven’t studied the impact of metallosis sufficiently. It is nothing to be worried about at this point.”

Sadly, this isn’t true. And it’s not the best medical advice. There have been several studies over the years that looked at metallosis in the body derived from metal-on-metal hip components. The first incident of metallosis from MoM hip implants was reported in 1971. Since then, doctors have been reporting the higher incidence of metallosis in patients who received MoM artificial hip implants. Several scholarly studies have been conducted, including a recent one whose results were published this month examining the impact of metallosis on the cells of patients.

What Is Metallosis?

Metallosis is a serious medical condition involving the deposit and build-up of metal debris in the soft tissues of the body. Metallosis has been shown to occur when metal components in medical implants rub or scrape against each other. Imagine the metal cup and the metal ball in an artificial hip grinding against each other day after day, for months and years. Very tiny metal shavings can be scraped away and released into the human body. Over time, these tiny shavings can build up alarming metal levels in the blood. It is common in hip replacements but also occurs in other joint replacements.

The Latest Study on Metallosis

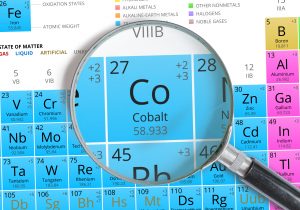

In the August 2016 edition of Biomaterials, an international research team looked at the physical impact of metallosis on the body. They studied metal-on-metal hip components made of cobalt and chromium and/or molybdenum alloys (CoCrMo). The study confirmed that use of these hip components can lead to the “release of wear products such as metallic particles and dissociated metal species, raising concerns regarding their safety” for orthopedic surgeons and patients. The study showed that release of these metal particles in the body are capable of producing problems on a cellular level, and can cause “aseptic osteolysis” and other health problems. Osteolysis is the destruction or disappearance of bone tissue.

In the August 2016 edition of Biomaterials, an international research team looked at the physical impact of metallosis on the body. They studied metal-on-metal hip components made of cobalt and chromium and/or molybdenum alloys (CoCrMo). The study confirmed that use of these hip components can lead to the “release of wear products such as metallic particles and dissociated metal species, raising concerns regarding their safety” for orthopedic surgeons and patients. The study showed that release of these metal particles in the body are capable of producing problems on a cellular level, and can cause “aseptic osteolysis” and other health problems. Osteolysis is the destruction or disappearance of bone tissue.

The study also examined the impact of metallosis on “mesenchymal stromal cells.” These are multi-functional cells that can develop into several different cell types which produce bone, cartilage, muscle or fat. According to the study, metallosis interferes with this cell development and can cause serious problems and “impair osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.” That’s a mouthful, but it’s not good.

Importantly, the study concluded by saying that the continued use of cobalt, chromium, and molybdenum alloys for joint replacement implants “needs critical reconsideration.”

Dr. James Pritchett is an orthopedic surgeon who writes a lot about the onset of metallosis following hip implants. He states that symptoms of metallosis include pain, instability, and increasing noise from the hip. In addition, metallosis may cause some or all of these symptoms: pseudo-tumors, nerve and thyroid problems, brain impairment, heart problems, depression and anxiety, visual impairment, rashes, infection, and implant loosening.

The Takeaway

The takeaway is that more and more studies are showing that high metal levels in the blood are a bad thing. The recent study in Biomaterials journal points to harmful changes that metal levels can cause to the cells of human tissue, and that use of metal-on-metal components for artificial hips and other joints must be “reconsidered.” I hear that to mean: “discontinued immediately.” In any event, do not accept your physician’s offhand comment that your higher metal levels (even if only slightly higher than normal) are of no concern. Get a second opinion. Metallosis is not a healthy condition. Good luck.

Note: This post does not reference any individual person or client. The information is general and is derived from many circumstances over several years.

For further information, check out the Biomaterials website. Biomaterials is an international journal covering the science and clinical application of biomaterials. But be warned: these are people with high levels of very specific knowledge. Pack a medical dictionary.

North Carolina Product Liability Lawyer Blog

North Carolina Product Liability Lawyer Blog